Hoi Erik,

Dat de giraf speciale kleppen heeft in de aderen weet ik, dit voorkomt terugstromen van het bloed in het hoofd wanneer de giraf bijvoorbeeld drinkt...

Dat de schedel een belang heeft in de regulatie van de bloeddruk lijkt mij vooralsnog wel waarschijnlijk.

Om kort te gaan, en ook om beter uit te leggen wat ik bedoel:

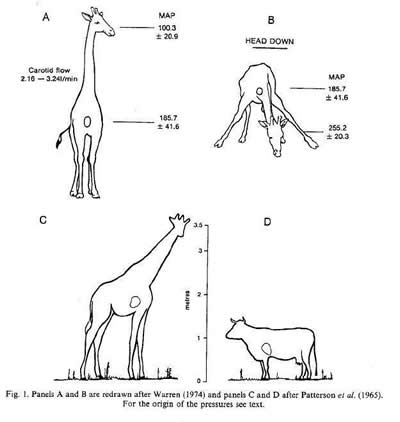

1) Worden de hersenen van de giraf doorbloed doordat het hart een enorm sterke pomp is?

2) Of is het hart misschien wel een sterke pomp, maarrrrr!, werken de hersenen en de slagaders en aders als een hevel? (siphon)

Dit plukte ik van een heel mooie site:

http://www.bio.davidson.edu/people/mido ... arvein.htm

The jugular vein and its offshoots contain numerous one-way valves to prevent blood from back flowing to the brain, when the head is lowered. Acting as a blood reservoir, the jugular vein is large (2.5 cm in diameter), and elastic so that it can stretch, counteracting the force of gravity on the blood. Muscle fibers surrounding the veins leading to the heart slow the flow of blood when the head is raised.

The jugular vein pressures in the giraffe are +14mmHg near the top and decreases linearly to about +4mmHg at the bottom. These data are contradictory to a model which supports a fluid column in which pressure increases toward the bottom. The best explanation for this phenomenon is that blood pressure in the jugular vein is influenced by external tissue pressures. This leads to the conjecture that there is higher tissue pressure at the top of the neck due to the giraffe’s tight skin. This tight structure would exert the highest pressure at the narrowest point near the head than lower down according to the Law of Laplace. (Seymour 2000)

Experimental measurements of the jugular vein in upright giraffes reveal an internal pressure somewhat above atmospheric pressure which increases with height above the heart. When these measurements are applied to a simple model of viscous flow in an inverted U-tube it was found that data was inconsistent with a siphon model which suggests blood vessels in the head and neck are effectively rigid such as a siphon. These observations however reveal that the veins of giraffes are collapsible and have a high flow resistance. A calculated flow rate of 80mL/s is about twice the flow rate estimated in a normal giraffe jugular vein, which if true would mean that cerebral blood flow is limited by downstream conditions (Pedley et al. 1996).

Dus, collapsible (slappe) vaten duiden op een mogelijk belang van de schedel, immers anders zouden de vaten ook af en toe kunnen dichtvallen, met alle schade van dien.

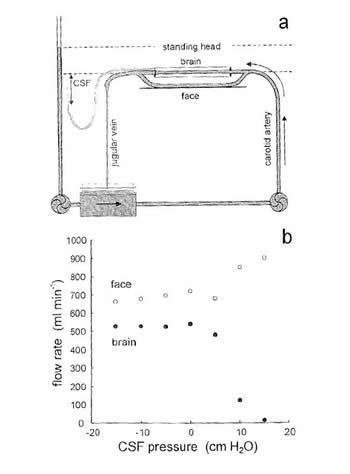

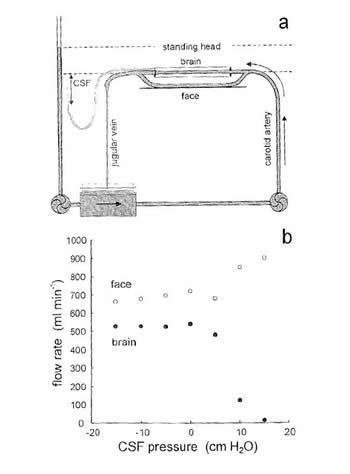

Dit wordt tevens gesuggereerd uit het bijgevoegde figuur (ook van site) waar te zien is hoe een toename in cerebrospinale vloeistofdruk (voorbij de nul!) de vaten van het brein van de giraffe kennelijk dichtdrukt.

De auteurs zijn zelf ook van mening dat overigens er geen siphon werking is:

Negative pressures cannot occur in collapsible vessels of the head unless they are protected from external structures such as the cranium and cervical vertebrae. If the cerebral-spinal fluid has a negative pressure it can prevent cerebral circulation from collapsing, and allow spinal veins to return blood to the heart in rigid vessels. Cephalic vessels outside of the cranium however are collapsible so there must be a positive blood pressure to establish flow in the system. These pressures observed in the collapsible vessels are a result of pressures exerted by surrounding tissues.

To disprove the siphon-like model of giraffe circulation tubing analogues can be set up to model this mechanism. The principle of a siphon is only conceivable if the vessels were prevented from collapsing either by enclosure within a rigid compartment or attachment to structures that would hold them open. Conceivably, the jugular vein could be protected from complete closure if they occurred between taut muscles or cervical bones. Structures around the blood vessels may on the other hand cause the vessels to close due to pressure they exert ( Seymour 2000).

The above figure demonstrates the effect of a rigid venous plexus and a collapsible jugular vein on the flow rate to the head of a giraffe at both below (a) and above (c) the level of the standing head.

The fact that the high pressure at the root of the aorta is higher than other mammals, suggests that a siphon mechanism is not an appropriate model because of the heart’s need to pump the blood uphill to the head. The central argument against the siphon mechanism is that the jugular vein is normally partly collapsed. This is evidenced by the rapid increase in pressure from 7mm Hg to 16mm Hg at distances of .3m to 1.2m above the heart respectively (Pedley et al 1996).

Mijn vraag komt er dus op neer:

Zien we aanwijzingen in schedels van grote fossiele gewervelden dat zij ook speciale regelmechanismen hadden voor bloeddrukregulatie in het hoofd?

En, zijn er grote gewervenden geweest met grote openingen in het cranium naar de hersenen toe?

Excuus dat ik het wat verwarrend breng.

J